Description

Skip James was one of the most influential early Bluesmen, but his importance as a stylist remained undiscovered until he was brought out of a long retirementby the Folk/Blues revival of the early 1960's. Born in 1902 and raised in Bentonia, Nehemiah Curtis James was brought up in a religious family: hisfather was a bootlegger who reformed and became a Baptist preacher. Skip learned piano in school but picked up guitar from his friend Henry Stuckey.In 1931 Skip was picked up by a scout for Paramount Records and he cut 26 tracks, of which 18 were released in a two day session at their Grafton,Wisconsin studios. These recordings presented a unique and haunting genius that influenced legendary bluesmen as Robert Johnson, Kansas Joe McCoy andJohnny Temple. But the recordings sold poorly, having been released during the Great Depression, and he drifted into obscurity.

We have included as online downloads Skip's 1931 recordings. The crackling sound of these rare recordings cannot obscure the brilliance of this seminalBlues master

After over 30 years retirement from music, Skip was rediscovered by blues enthusiasts Bill Barth, John Fahey and Henry Vestine. They persuaded Skip toappear at the Newport Folk Festival in 1964, where his renditions of his old songs were still powerful and moving. His performances as well as hisold and new recordings influenced a generation of new musicians: Eric Clapton, Alan Wilson of Canned Heat, Cream, Deep Purple, Chris Thomas King, AlvinYoungblood Hart, Derek Trucks, Beck, Big Sugar, John Martyn, Lucinda Williams and Rory Block to name a few.

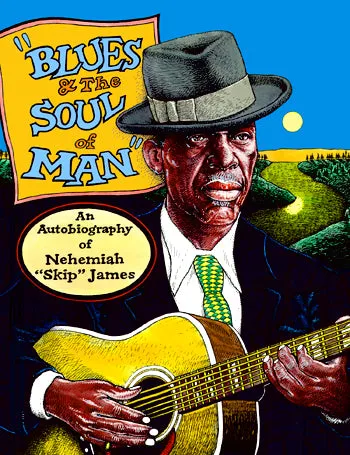

Books on legendary Blues musicians written by White musicologists tend to offer a subjective perspective on how the artists felt, thought or reacted. Atainted picture is captured that has more to do with the writer's social and musical experiences. This autobiography is different. The words, thoughtsand feelings come directly from the artist's lips. This is the story of Nehemiah "Skip" James told by Nehemiah "Skip" James.

Level 1 • 128 pages • Download Audio Files

Review: Skip James was the epitome of a bad day. His Mississippi blues, the model of brooding intensity, could grow so dark and haunted as to fade into black, stringing together famously gloomy strands like “I’d rather be the devil, to be that woman’s man” or “people are driftin’ from door to door, can’t find no heaven, I don’t care where they go.” Robert Johnson mirrored “him” as “Hellhound on My Trail.” This came later from the same cauldron as did “Devil Got My Woman.” Skip had already landed on the “Killin’ Floor” decades before Howlin’ Wolf ever did.

“Blues and the Soul of Man’s” 130 jumbo pages rise to the challenge of James’ mystique. Unlike Stephen Calt’s 1994 biographical “I’d Rather Be the Devil”, this autobiography lets James tell his own tale. No poetic embellishment; no outsider spin; only raw dialogue transcribed from hours of interviews. Here, music journalist Eddie Dean’s introduction admirably does its job by first encapsulating Skip’s history as well as embedding the hook for what follows.

James – himself - then picks it up from there. His stream-of-consciousness rambles from dead jaybirds, rolling-the-belly, poisoned whiskey, hoodoo root doctors, pickled pork, and barrelhouses to minor chords, God, Satan, grappling over what exactly the soul of a man is, and, of course, his famed 1931 Paramount sessions. Life philosophy spills over the edges. Switchblades get drawn, pistols fired, and personal tours given of violent levee and lumber camps. “Cherry Ball Blues,” “Cypress Grove Blues,” “Illinois Blues,” “If You Haven’t Any Hay Get on Down the Road” and “Devil Got My Woman” get (partly) deciphered. To round out the experience are music/tab roadmaps to a few choice songs and, better still, online downloads of James’ 1931 recordings. Best of luck trying to put this down.– Dennis Rozanski/Blues Rag

Review:“Blues & the Soul of a Man”: An Autobiography of Nehemiah “Skip” James, from interviews with Stephen Calt, edited by Stefan Grossman, with an introduction by Eddie Dean (Mel Bay Publications and Stefan Grossman’s Guitar Workshop). The Mississippi blues singer Skip James (1902–1969) first recorded in 1931; in 1964 blues devotees found him in a hospital in Tunica and brought him north to perform at the Newport Folk Festival, where despite not playing for decades he shocked the crowd with the ghostly curse of “Devil Got My Woman.” He was a difficult man who considered himself a great artist and most others pikers or pretenders — and he was a great artist.

The blues scholar Stephen Calt (1946–2010) spent countless hours with him, with the intent of compiling an autobiography; instead he published I’d Rather Be the Devil: Skip James and the Blues, a deeply researched book that at times spilled over into near dementia, as if what Calt wanted to say was that unlike Robert Johnson, who supposedly merely made a deal with the devil, James was.

By editing Calt’s interview into a coherent and startling narrative, Stefan Grossman has produced a historic and invaluable addition to the story not only of the blues but of the American tradition of radical individualism, a book that despite less than 75 pages of narrative can be placed next to Theodore Rosengarten’s All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw, a big, indomitable book of the voice of the Alabama farmer Ned Cobb (1885–1973 — Rosengarten changed his name to protect his family from reprisals from whites), who would have had a lot to say to Skip James.

“[Y]ou’re talking to the walking encyclopedia,” James says at one point, and in tale after tale he brings you into his life, often shaping his stories around lyrics from his songs, not as if the songs are autobiography, but as if they’re philosophy lessons. “But you take guys like John Hurt and Son [House],” James said of the two Mississippi blues singers from the ’20s who he was often paired with in the ’60s, “they’re just shaky. A white could tell ’em: ‘Go ahead and put your head in that hole nigger,’ and they’ll cower to that extent.”

Calt made much of the people he says James murdered as a younger man, and James does describe one fatal shooting, as self-defense, a death that in his account brought no charges or even blame — it happened at a work camp, and James didn’t even leave. But Calt also lied. At one point he takes James’s song “All Night Long” as proof that James was wanted for murder in Louisiana, and implies that James hinted that was so. What James actually said is not just a corrective, or, you can hope, the righting of a literary blues crime. In its way, it’s another version of the song.

“If it had been just a few Negros like my daddy and myself and a uncle or two I got, this riot” — the Civil Rights movement: James was found the same day the SNCC voting rights activists James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman disappeared, murdered in Mississippi by the Ku Klux Klan —wouldn’t been existin’ now: everything woulda been settled fifty years ago. […] You know, the Southern white folk at that time didn’t wanna see the colored fellow with nothin’ but a shovel or a hoe-handle or plough-handle in his hands, and a mule to pull it. Some places, they tell me, down in Louisiana there, they made the Negroes pull ploughs. And they wouldn’t give ’em no place to lay down; just put ’em in a stall like they did mules and give ’em so many ears of corn. Sure! That was long about 1910 or 1912; I was just a kid when I heard all that kinda stuff. […] Now, I never did go down there and investigate. If I hadda did, they woulda had to kill me, understand.

Just like I sang in All night long:

I’m goin,’ I’m goin,’ comin’ here no more

If I go to Louisiana mama, they’ll hang me sho’ …

“That’s the time this riot oughta been organized,” James said. “It should have originated right then. If you speak for yourself, and you know you’re right, it’s always best.” – Greil Marcus/Los Angeles Review of Books